Ofsted: reformation or revolution?

Are we looking at a #quietrevolution in the way in which schools are held accountable for their performance?

Currently schools are told on the afternoon before inspectors arrive, giving them the opportunity to prepare into the night before Ofsted actually enters their school. However, under new plans schools could get just 15 minutes’ notice before Ofsted inspectors arrive on their doorstep.

This has led to a strong reaction from school leaders and unions. Nick Brook, National Association of Head Teachers deputy general secretary, said: “If an inspector is in a school, reviewing documentation and speaking to staff then the inspection has already started. Inspection is routinely cited as one of the most stressful situations that a school leader will face. Moving to a system with only a couple of hours’ notice will send anxiety levels through the roof.”

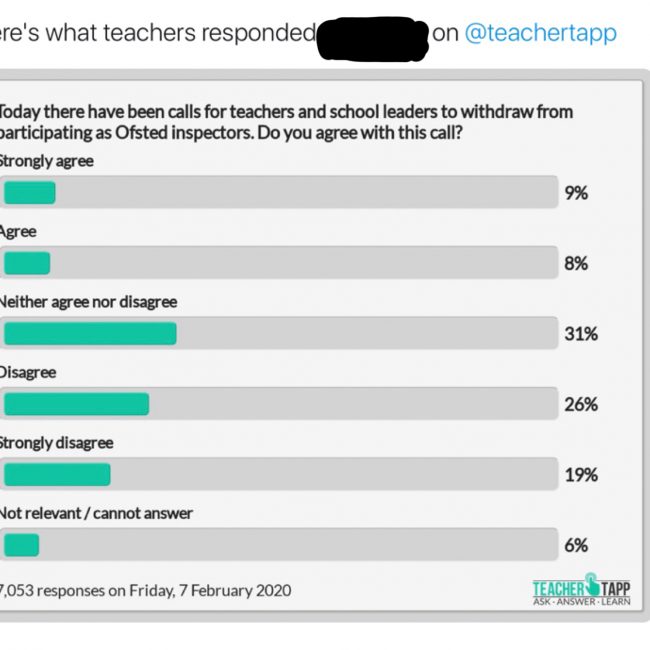

Headteachers’ Roundtable agreed to formally request all school-based employees to resign as Ofsted Additional Inspectors, with immediate effect. They have called on unions and other professional associations to recommend this “quiet revolution” to members, and “to ensure no school-based employees involve themselves in inspection.”

In response, the Leadership Council of the National Education Union has pledged its support of the #PauseOfsted campaign and is advising NEU members not to work for Ofsted as additional inspectors.

Stephen Tierney writes:

“To truly improve our schools, we need a system founded on the principle that there is no single way to improve a school. Peer-to-peer accountability is far better suited to reducing the significant variability found within so many schools and between them, and a much more ethical and effective use of school leaders’ time.”

Jeremy Hannay wrote in a recent Tweet:

“Ofsted is flawed

Deeply

And is leaving in its wake

A calamity of broken schools

Leaders

Teachers

Children

It needs a rewrite. Allowing it to continue as is while we rewrite only serves to increase the damage to our people. We need to #PauseOfsted”

Now is the time for all interested in school improvement to be asking:

Are Ofsted inspections really the best way to improve school performance?

Is this the time we make fundamental changes to school accountability?

Ben Newmark tweeted: “The fundamental problem with @ofsted has always been that its performativity exceeds reliability. No framework is going to change that. Solution: lower the stakes. We already have high stakes league tables and other performance measures. Ofsted doesn’t need to do this too.”

Is part of the problem, a big part of the problem, that school performance is reduced to a one word judgement?

This is how Ross Morrison McGill, aka @TeacherToolkit puts it: “On the point of grading schools, the profession must be aware that there will be many policymakers who want to keep such a tool for, largely unfounded, purposes. Ofsted’s new framework, perhaps friendlier, is already regurgitating inequality. Don’t fall for it.”

“I am tired of hearing that OFSTED is not the reason for good headteachers losing their jobs when we all know so many examples of this happening. Indeed, even when an OFSTED report is complimentary about the leadership of the headteacher, the pernicious impact of an unfavourable overall judgment has frequently led to the head quietly leaving, and the system losing a good school leader.” Writes Ros McMullen, headteacher with nearly 20 years experience.

She goes on:

“For me the problem is threefold:

1. Applying judgement is not something about which we can be scientific or consistent, and variability is only to be expected. We should not, therefore, attempt to make any judgments other than those which can easily be judged to meet or fail a set list of criteria.

2. The high-stakes nature of an OFSTED judgment creates worry and fear which negatively impacts workload, stifles innovation and destabilises school leadership and school improvement.

3. Curriculum is our most important input and it needs to be of the highest quality, but this necessitates it being in a constant state of review and improvement according to the context and need of those we serve; not something that can be reduced to any checklist.”

Writing in The Guardian Emeritus Professor Michael Bassey: “The government should realise how professionally committed teachers are to the children they teach and how hard they work. Standards rise because young people choose to study hard, are taught well by their teachers, are encouraged by their parents, and influenced by a positive climate towards schoolwork by their peer group of classmates. Advisory inspection may help: punitive inspection doesn’t.”

Is John Cosgrove correct when he describes Ofsted as toxic? “It destroys lives, and in doing so, harms children’s education. I acknowledge that this is not the intention, and never has been. There are many good and decent people who genuinely believe in ‘improvement through inspection’. But the reality cannot be avoided.”

However, some are urging caution not revolution. Michael Tidd for example; “My understanding is that Stephen [Tierney] wants ofsted stripped back to a admin role and peer review to replace it. And it doesn’t seem to be the change in the framework that’s the issue but its implementation.

In truth, I’m not sure that there’s much agreement in the profession about what an improved inspectorate might look like. Which isn’t a very good starting point for a conversation”